For many years, I’ve been talking about the need to reform global drug laws and to put people’s safety, health and wellbeing at the centre of drug policy. There has been remarkable progress as some governments have moved towards cannabis regulation while others made harm reduction the primary goal of their efforts, effectively moving drug use from the realm of criminal justice to the realm of public health.

But in much of the world, prohibition is still the law of the land, imposing draconian criminal sanctions, including the death penalty, for non-violent drug offences. Much of this zealotry is rooted in widespread misconceptions of those who use illegal drugs – nearly 250 million people in 2016, according to the UN. These misconceptions are not only wrong, they are dehumanising, and they kill people.

As a member of the Global Commission on Drug Policy, I have long made a point of meeting with people who use drugs, to learn more about their personal circumstances, the support they need and seek, and how their drug consumption is affecting their lives, if at all. While I’ve met many who battle dependency or addiction and some who didn’t survive, I know countless people whose drug use is casual, recreational, and entirely inconsequential.

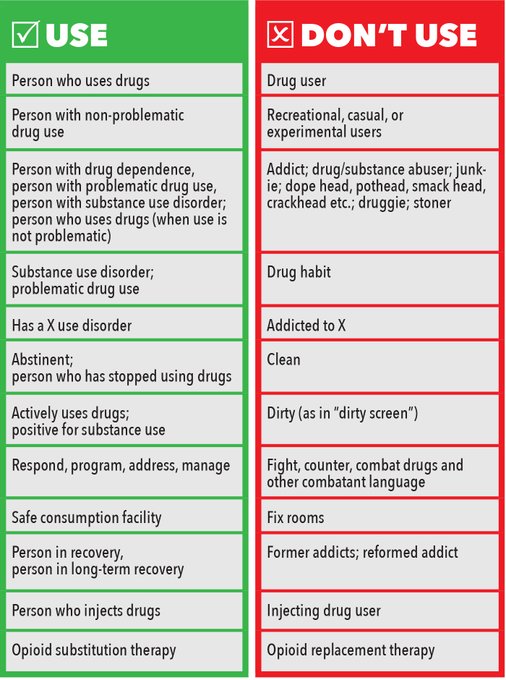

Of course, drug misuse is a serious challenge, and I find few things as shocking as the staggering and rising death toll of America’s opioid epidemic. But these real crises are needlessly exacerbated by the vicious cycle of stigma, marginalisation and criminalisation that so dramatically uproots the lives of those who use drugs. It often begins with labels. People are called “junkies” and “criminals”, even though using illegal drugs is the only crime most of them are ever guilty of. What often follows is rejection, expulsion, and abuse. For many, including those struggling with addiction, moving into the shadows where drug use is hidden from public view seems to be the only viable option left. But this forced retreat into the world of unknown substances, unsafe consumption and lack of medical support is part of the reason overdose deaths remain so high. And the ongoing criminalisation of people who use drugs only makes things worse. Fear of police harassment, criminal persecution, or imprisonment keep thousands from seeking help when they need it most.

There is no question, sensible reform means breaking barriers, including those in people’s heads. Today, I’m quite encouraged that the Global Commission has released a new report that seeks to do just that. The World Drug Perception Problem sets out to counter the prejudices and stereotypes about people who use drugs that are at the heart of disproportionate and ineffective policies in many parts of the world.

The report makes a number of helpful and sensible recommendations for change, but two stand out in my view: firstly, it should go without saying that all drug policy must be rooted in scientific evidence and accurate information. Stereotypes, fear and misinformation spread by politicians, by the media and in the broader public must be confronted and challenged. Secondly, respect for human rights and concern for health and safety should be policy priorities, so that harassment, discriminatory practices, marginalisation and criminalisation can be stopped once and for all.

A few years ago, I visited Sydney’s Medically Supervised Injecting Centre (MSIC), the only facility of its kind in the Southern Hemisphere. I remember meeting one of the clients, a woman who really moved me with her thoughts: “We might be junkies, but we’re all redeemable. Anyone that has a pulse is redeemable, we just need a chance.”