PRI has launched its annual flagship publication, Global Prison Trends 2018. Here we publish the foreword to the report, written by the Rt Hon Helen Clark, a Member of the Global Commission on Drug Policy, Former Prime Minister of New Zealand, and Former Administrator of the United Nations Development Programme.

PRI has launched its annual flagship publication, Global Prison Trends 2018. Here we publish the foreword to the report, written by the Rt Hon Helen Clark, a Member of the Global Commission on Drug Policy, Former Prime Minister of New Zealand, and Former Administrator of the United Nations Development Programme.

Read foreword on the website of Penal Reform International

Every year, Global Prison Trends by Penal Reform International (in collaboration with the Thailand Institute of Justice) provides us with a global view on the state of prisons. And, every year, this report is, unfortunately, hardly a surprise – we read about the degrading conditions in which people are imprisoned, and about their growing number. Yet the level of crime in most societies is constantly decreasing. The question that remains unanswered, therefore, is why our societies focus their response to unlawful behaviours so often on prison? Where is the proportionality in sentencing when we punish nonviolent offences with lengthy prison sentences? Is this the only response we can offer?

The chapter on drugs and imprisonment in this report highlights that a high number of prisons in the world are overcrowded due to the incarceration of people for drug-related offences, in particular non-violent offences involving use and possession for personal use. This directly reflects our contemporary addiction to punishment and showcases the disproportionality of punishment in relation to the offence. The use of harsh prison sentences for people who use drugs or for those who play a minor role in the drug trade also shows the inefficiency, limitations and perverse effects of current drug control policies. Not only are punishment and incarceration becoming the sole instruments used to enforce the law, but also they are serving to implement moral norms which have no link with the reality of the offence that they are supposed to punish.

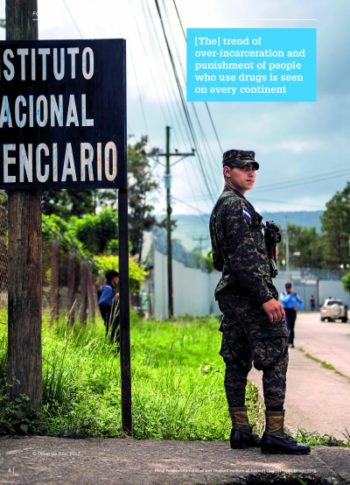

This trend of over-incarceration and punishment of people who use drugs is seen on every continent. The deep impact it has on prison systems and on people in prison and their communities has sparked the current global debate on drug policy reform. In recent years, more and more countries have been introducing amendments to their drug laws; for example, by decriminalising the use of drugs in Norway and Colombia, and by replacing prison terms with monetary fines in Ghana and Tunisia or with community service, as envisaged in Senegal. Other countries have gone even further. Ecuador gave an amnesty to drug couriers and released thousands of prisoners. Countries that have traditionally adopted harsh stances on drugs, such as Malaysia and Iran, are reviewing their death penalty policies for drug offences, and removing people from death row.

These changes and reforms are being discussed and implemented in a global environment that remains highly stigmatising, where drugs are still considered ‘evil’ and prohibition approaches prevail. They are therefore born out of a real need – the need for societies to stop exposing their citizens to greater risks from arrests related to drug use than come from the act of using drugs.

The need for reforms was also highlighted at the UN General Assembly Special Session on Drugs held in 2016. In their decisions there, member states called for more proportionate sentencing and for alternatives to incarceration. At the Global Commission on Drug Policy, we call for these commitments to be implemented, taking account of the fact that over-incarceration as a result of out-of-date drug policies stalls progress on implementing the Sustainable Development Goals, notably for Goal 3 on health, Goal 5 on gender equality, Goal 10 on reducing inequality, and Goal 16 on peaceful societies. Drug policies need reforms, and there are two urgent ones to enact. First, we need to accept that behaviours and actions of others that are not aligned with our own moral perspectives do not need to be turned into criminal offences. Second, we need to introduce proportionate sentencing and alternatives to imprisonment for minor drug supply-related offences. This will ease pressure on prison systems so that they can fulfil their purpose as set down in the UN Nelson Mandela Rules: to play a rehabilitative role and focus on social reintegration, and to distance from the criminal justice system those who should not be subject to it, including people who use drugs.

Download Global Prison Trends 2018